Charlie was the unloved love-child of the beautiful flame-haired Alice Anderson and the wild and stubborn James Johnston.

Alice was tall and willowy and full of gentle grace. The oldest of 6, auburn-haired and softly freckled, she could have had any boy, and there were any number of boys that would have been acceptable to her family, boys with property, boys with futures. But Alice wanted James, wanted James badly enough to ignore the circumstances and discard her fear.

James was smart, bored, unpredictable, and beautiful in the surprisingly unexpected way young men can often be. Tall and wiry, dark-haired with icy blue eyes, James simmered with rebellion, impatient with his life and the rules imposed on him. James wanted Alice, wanted her badly enough to take her in spite of his family’s expectations for him…

James and Alice were the children of two feuding Appalachian mountain families, entangled in a conflict that was not of their own making, but that ruled their existence in every way possible. It was unavoidable, it was undeniable and it was obligatory.

James was 17, Alice just barely 15…

They met clandestinely, sneaking off to be together, equally cautious and careless, running through the verdant mountain forest, seeking out the quiet spots to meet. They loved each other passionately. They chose to live for the moment and to deny the possibility of disaster. They had plans, their lives would be different and they could and would make a life together, families be damned…

Alice had just one brother, the darling baby boy. Auburn-haired and green-eyed, he was his parents’ joy. I’ve never known his name, I don’t think my mother does either, he is always just “the younger brother” or “the youngest” when my mother tells the story.

This brother of Alice’s was out squirrel hunting early one fall morning. Unfortunately, it was also a morning when James and Alice had lingered a bit too long, parting well after sunrise. James spotted Alice’s brother walking through the wooded hills with a shotgun…

Perhaps James worried that the Andersons knew about Alice and him. Perhaps he thought the boy was hunting him. Perhaps he was just too wild and full of anger. He shot the younger brother and killed him. The boy was only 12…

James fled, fearing not the law, but the Andersons. Perhaps he didn’t know, perhaps in his fear it would not have made any difference, but he left a pregnant Alice behind. He was only 17…

Alice had to live with the consequences. She was held accountable for the death of the younger brother. She was shamed and scorned and her pain made out to be a justly deserved punishment for her wicked ways. She was made to understand, deep in her bones, that she was no good, never would be, and it was all her fault. She was only 15…

At seventeen she handed the 2-year old Charlie to his grandmother and fled the dismal realities of her fall from grace, the now bloody feud between the families, and James’ desertion of her and the child. After she left the family’s harsh and unforgiving spirit enveloped Charlie. He was never loved, never treasured as a child should be, never treated as anything but living evidence of a distasteful and shameful event that robbed the family of their precious son. Used for farm work from the time he could carry a bucket of feed across the farmyard, he was sent to live with a childless relative and his wife. At 14 he lied about his age and entered the army, fleeing the hell that was his childhood, seeking order and sense and purpose in the rigorous life that was the army in 1920. Charlie’s life was going to be perfect.

He was an extremely gifted, absolutely ignorant boy whose first pair of shoes were the boots he received in basic training. For the first time in his life, he had enough to eat, was adequately clothed, and felt appreciated as a human being. The army was the family he had desperately wanted, passionately needed. They taught him to read – he’d never been to school. They trained him, feeding his mind as they fed his body. He became a sharpshooter, winning medal after medal after medal – an entire cigar box full of them. Discovering an innate talent for math and science, he became a specialist in the field of radio and later, television. He married a wealthy Irish girl from Boston and had three children with her. Charlie’s life was becoming perfect.

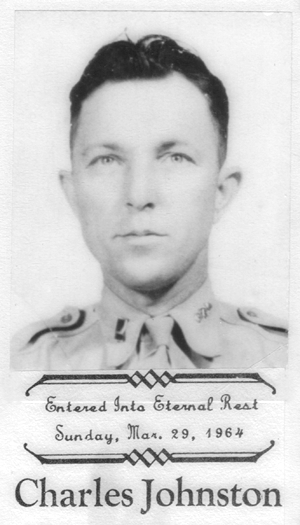

Other than this obituary photo I have only one photograph of my grandfather. He is sitting on a scuffed leather hassock, with his favorite bird on his shoulder, happy and playful and so very handsome. He was cheerful, optimistic, and unflappable. When he retired from the military, as a colonel, he took a position with the RCA Corporation and quickly advanced in the company, eventually ending up in charge of a large television manufacturing plant in southern Indiana. The family moved into their first home –having lived in military housing until this point. There was room for a garden. Charlie had a woodshop. He was a success in every imaginable way. Charlie’s life was perfect.

In the midst of all his happiness, Charlie slowly became rudderless, losing interest and purpose and meaning in his life, becoming once again the lost and alone soul, managing in his professional life, but floundering at home. His difficulties, “Charlie’s trouble”, as it was sometimes called, was never diagnosed, never treated, never dealt with in any constructive manner, never seen as anything except failure and disgrace. He and my grandmother were Catholic; they stayed married even when he became cruel and distant. She moved out but never filed for divorce.

Charlie was alone for the last few years of his life. His children visited when they could, but they had young families of their own, and he could be difficult, unreasonable, and unpredictable. He often scared my brother and me. I’m sure he didn’t mean to, but he did. Charlie died alone one brilliant Sunday morning in April. The cause of death was determined to be heart failure, the result of mixing alcohol with the medications he used to control his chronic asthma. I think his heart was simply broken beyond repair.

It was 1964.

He was 58.

Recent Comments